If your child aces the eye chart at the pediatrician’s office, you might assume her vision is just fine. But some common vision disorders can’t be detected by a standard eye exam — and could be holding your child back in school.

When Jennifer Stone Hopp’s son Ethan was in first grade, his teacher told her that he had “all the tools to read,” but he “just wasn’t pulling it together.” When Hopp and her husband tried to work with him on reading at home, he’d refuse. “He skipped words everywhere. He couldn’t focus. We’d negotiate: ‘You read a line, then I’ll read a line.’ It was brutal,” she says.

In the second grade, Ethan was diagnosed with mild farsightedness and got glasses. The Hopps thought his reading would improve — but nothing changed. As elementary school progressed, Ethan continued to struggle as the family cycled through a series of professional tutors. “He had so much trouble with any kind of reading — even word problems in math class were difficult,” says Hopp.

At the beginning of fifth grade, Ethan broke down. “He said, ‘I work so much harder than the kid who sits next to me, and he gets A’s, but I’m getting C’s and D’s. What’s wrong with me?’ ” recalls his mother. She took him to yet another reading tutor — the only one in their New Jersey town that they had not yet visited. But unlike the others, this tutor didn’t just sign him up for regular sessions. “I don’t work with anyone unless I’ve checked their vision with a Visagraph test first,” he said.

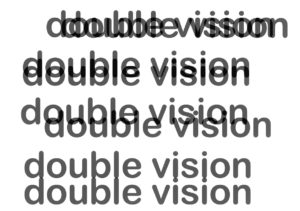

A Visagraph uses specialized goggles that measure how the eyes work together when someone is reading — a process called binocular coordination. The test showed a significant problem with Ethan’s eye coordination, and the tutor referred Hopp to a nearby developmental optometrist, who diagnosed Ethan with a condition known as convergence insufficiency (CI). “He said, ‘It’s so severe that Ethan actually has double vision when he reads.’ I turned to him and said, ‘You see double?’ and he said, ‘Yeah.’ He’d never said anything — I guess maybe he thought that’s how it was for everyone,” Hopp says.

Binocular Vision

Some vision disorders that affect children — such as myopia(nearsightedness), amblyopia (lazy eye), and strabismus (a misalignment of the eyes) — usually can be detected on standard pediatric eye exams. But CI is different and easy to miss or misdiagnose.

It’s one of a group of vision disorders that have nothing to do with the function of the eye itself, but rather, with how the eyes work together. “These aren’t really vision problems as much as they are brain problems,” says Barry Tannen, the developmental optometrist who treated Ethan. “When we read, the brain needs to give our eyes signals to focus, converge, track, or not track — and this all happens because of a higher cortical mechanism that, in some people, we have to train the brain to control.”

In people with CI, the eyes have a strong tendency to drift outward when reading or doing other work close up. People with a related disorder, accommodative insufficiency (AI), have difficulty changing their eyes’ focus from near to far, or vice versa. Yet another condition, oculomotor dysfunction, occurs when the six muscles around each eye, which precisely control eye movements, do not work properly together, affecting the ability to do such things as hold the eyes steady or follow a moving target.

CI is the most common of these conditions, and studies show that it affects about 5% of the population. When other conditions like AI and oculomotor disorders are included, Tannen estimates that one in 10 students in any given elementary school classroom may have at least one disorder of binocular vision. (Many people have more than one.) These children frequently test as having perfect 20/20 vision on a pediatrician’s eye chart — but like Ethan, they struggle in school and find reading an exhausting, painful chore.

“The problems often really show up around second or third grade, when children start having to read books with smaller, more closely packed texts, and they do more reading for classes like science or social studies,” says Christine Allison, a professor of optometry at the Illinois College of Optometry and the president-elect of the College of Optometrists in Vision Development. “These children are often diagnosed with ADHD since they can’t sit still and look at a book — because it’s too hard to keep their eyes in line, and they can’t comprehend if they’re not reading well. In other cases, parents or teachers may assume that it’s behavioral — that their child is just rebellious or lazy and doesn’t want to read.”

Could Your Child have a Binocular Vision Disorder?

If your child struggles with reading and complains that it’s difficult or painful, yet sails through the pediatrician’s eye chart with no problems, then a binocular vision disorder could be to blame. If you pick up on any of these signs and symptoms, consider seeing a developmental optometrist for testing. (Find one near you at covd.org.) Does your child:

- Complain that her eyes feel tired or uncomfortable when reading (or doing other close work)?

- Get headaches or feel sleepy when reading?

- Have a hard time concentrating when reading?

- Have trouble remembering what she’s read?

- Rub her eyes a lot when reading?

- Act out, especially when asked to read?

- Have double vision when reading?

- See words move, jump, or appear to float on the page?

- Notice that words blur or come in and out of focus when reading?

- Lose her place on the page often, or have to reread the same line of text?

- Resist reading and avoid it whenever possible?

You may have noticed some of these symptoms yourself. But for others — like the double vision and the floating words — you’ll have to ask your child. They will complain when they have a headache or their eyes hurt, but like Ethan, they don’t necessarily know that it’s not normal to see double when reading or have words appear to move on the page.

Treatment

This can all be treated effectively. Sometimes children with one or more disorders of binocular vision may also need special glasses or prisms, but studies show that the most effective treatment is vision therapy — in-office exercises with a trained therapist, along with at-home reinforcement.

That’s what Tannen did with Ethan. Every week, Ethan visited the doctor’s office and went through a set of exercises with a vision therapist, and then he repeated those exercises at home throughout the week. Typically, vision therapy can last from 12 weeks to more than a year. Ethan’s case was so severe that more than 2 years passed before the problem was resolved.

“But we started seeing improvements very quickly,” says Hopp. “Ethan had actually developed an eye infection called blepharitis, because he was rubbing his eyes so much, and within a month that went away and never came back. And it wasn’t long before his behavior really started to turn around — he became much more calm and patient. Now, he can concentrate better in school, and his logic is so much better.”

Now 12, Ethan still works with a tutor to make up for vocabulary he missed during the first few years of elementary school. He’s been admitted into his school’s advanced math class, and he is determined to qualify for advanced history as well.

“And he’s organized now. The teachers used to complain about his desk, but now it’s all orderly and his backpack is the most organized thing I’ve ever seen,” Hopp says. She admits that Ethan still isn’t a passionate reader, but he no longer struggles with it: “He prefers nonfiction — recently he picked out a book about diseases. It’s all about finding things that interest him.”

Tannen stresses the importance of early diagnosis and treatment for CI, AI, and other binocular vision disorders.

“It’s about much more than reading. These kids take a huge hit in their self-esteem. It changes the way a child views himself,” he says. “You can do vision therapy and correct the problem when you’re 20, but you can’t go back to third grade. The successes or failures you had when you were that young — they stay with you.”

See What Your Child Sees

To get a sense of what a child with binocular vision problems sees when trying to read, Allison suggests the following exercises:

- To mimic oculomotor problems, try reading a few lines of text that is written vertically, rather than horizontally.

- For accommodative insufficiency, try crossing your eyes so the print appears double or blurry.

- Convergence insufficiency is harder to imitate on your own (optometrists have computer screens that mimic the effect), but you can get a sense of the fatigue and eyestrain that happen if you try to read something complicated and technical, in very small type, while covering one eye.

WebMD Magazine – Feature Reviewed by Hansa D. Bhargava, MD on April 06, 2017

Anxiety and depression in your child may be the result of a visual disorder. The physical, mental, and emotional changes that are going on at this age make it difficult to manage a disorder they usually don’t even know they have. Compensation, and particularly in school, is much more successful at a younger age, a much simpler time in their lives. Intelligent, bright children study for hours and still struggle. They often feel that no matter how hard they try, they will never be “good enough.” With so much effort going to their studies, they may feel they are missing out on having fun and being a kid. They feel resentful of their parents but mostly take these feelings out on themselves — feeling they are not smart enough, not good enough. This contributes to both anxiety and depression.

Anxiety and depression in your child may be the result of a visual disorder. The physical, mental, and emotional changes that are going on at this age make it difficult to manage a disorder they usually don’t even know they have. Compensation, and particularly in school, is much more successful at a younger age, a much simpler time in their lives. Intelligent, bright children study for hours and still struggle. They often feel that no matter how hard they try, they will never be “good enough.” With so much effort going to their studies, they may feel they are missing out on having fun and being a kid. They feel resentful of their parents but mostly take these feelings out on themselves — feeling they are not smart enough, not good enough. This contributes to both anxiety and depression.